On remembering to react

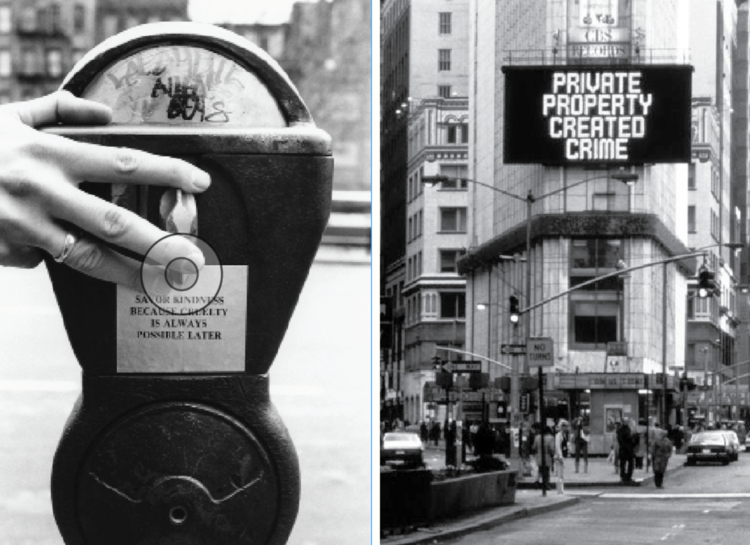

Projection by © Jenny Holzer, via DAZED

and the fear of pure feelings

There are different kinds of ways to feel afraid. Your heart sometimes beats faster, your body starts to tremble, you may struggle to catch your breath. In stillness you feel strangled, in movement you feel numb. Those are the obvious signs, the physical responses we experience when we feel threatened; at the peril of a situation that could potentially do us harm. Like an encounter with a beast in the wild, or a meeting with a stranger some place dimly lit, in a city we do not know. But not all fears are plainly manifested in the body. Some lie deep and dormant, entrenched by peripheral coercions that are naked to the eye. They are the obscure anxieties that linger in quiet, too still for us to sense.

They are the fears that keep us scared in silence.

I first encountered American artist Jenny Holzer’s work on a t-shirt in New York. It was wrapped in a see-through sleeve and sitting on a shelf in the design store of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). At the time, I didn’t know who Holzer was, but I knew that the t-shirt felt important. REMEMBER TO REACT, it told me through its plastic veil, in black font. Despite my aversion to slogan tees, I bought it and took it home. Not because I wanted to wear it, but because it reminded me of something that I needed to be reminded of.

Born in Ohio in 1950, Jenny Holzer never used to be sure if she could be, or should be, an artist. But despite these initial hesitations, Holzer’s work today exists largely in a dominion of its own. Most renowned for her conceptual, text-based installations, the artist once described her work as totalities designed for particular spaces.

It all began with a series of single-sentence statements called Truisms in the late 1970s. Posted by the artist at night on buildings across downtown Manhattan, the collection was written by Holzer to express ‘everything that could be right or wrong with the world’. Influenced largely by the reading list of the Whitney Museum’s independent study program, where she studied from 1976 to 1977, the series was made up of bold and, at times, contradictory statements, as plainly put as they were provocative—short but definitely not sweet. Completely anonymous and neutral in their style, each truism examines the social constructions of beliefs, morals, and truths, inviting readers to experience their own natural responses to the idea that is represented. A few years later, after Holzer produced two additional text-based collections, Inflammatory Essays and Living, her work took on a whole new shape and scale. In 1983, the artist launched her Survival series—powerful statements that explored the ways in which we respond to the world around us, rooted largely in themes of fear, insecurity, pain, and self-protection. The first of Holzer’s artworks to be written specifically for electronic signboards—to be displayed in very public spaces—the Survival statements were short and direct, arresting the attention of innocent passers-by. PROTECT ME FROM WHAT I WANT—projected on a 20 x 40 foot Spectacolor sign in New York’s Times Square—is one of the most famous. My t-shirt’s slogan, REMEMBER TO REACT, is another. In an article published by The New York Times in 1989, news editor Grace Glueck summarised Survival as follows:

‘In this series, she gives political instruction: ‘‘PUT FOOD OUT IN THE SAME PLACE EVERY DAY AND TALK TO THE PEOPLE WHO COME TO EAT AND ORGANIZE THEM’’; makes dire predictions for the human race: ‘‘YOU ARE TRAPPED ON THE EARTH SO YOU WILL EXPLODE’’; and advises those who live like automatons: ‘‘REMEMBER TO REACT.’’’

You could say that the latter three words spell out an instinct that seems too obvious to mention—much like remembering to breathe. To react, of course, should be an instinctual thing. An effect that rises within us when we encounter something pleasant, or when we are provoked. Yet in a world where we’re constantly barraged by words—big and small, kind and con- spiratorial, corporate and commercial—it can be hard to differentiate pure reactions from those that are experienced under the influence of some other hidden agenda.

Truisms by © Jenny Holzer, via DAZED

There is a difference between dressing to reflect who we are, and to reiterate the tastes of those who’ve been paid to influence our style. Buying shoes just because we like them, or because a label said just do it. Eating foods we crave, rather than those we’ve been told cater to recommended dietary requirements. Lying down to rest when our body tells us we’re tired, and popping pills to numb the stress that most likely arose because society frowns upon our slowing down. And voting in honour of our virtues, instead of casting a ballot for a candidate because a poster promised that she or he would make the country great again.

Amid the neon-lit maze of the directions and decisions mapped out for us, it’s not hard to slip into a consumeristic coma, especially when we’re made to feel as though we have no other choice—note the ease of pressing the love heart button on Instagram, and the absence of an alternative option. Or the forms with the selection of boxes we are allowed to tick, sans the space to write down what we really think. Encounter enough situations where your freedom of speech is tamed into the liberty to align with a carefully curated selection of words chosen by others, and it’s easy to believe that your own thoughts ought to resonate with the prefabricated cognisance. Easy, too, to forget how you really felt before you pressed the love heart button, or ticked the box that seemed like the most fitting choice. But when to like and comply are often the only options we are offered, it has to make you wonder.

Do we really exercise our right to react in a way that serves the self, and not the stimuli?

In 1974, German political scientist Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann proposed a theory she called the “spiral of silence” in an attempt to explain the ways in which public opinion is formed. In short, her spiral of silence refers to how people tend to remain silent when they feel that their views align with a minority belief. According to Noelle-Neumann, the closer a person believes their thoughts mirror public opinion, the more likely they are to speak. If their thoughts diverge too far from the norm, they tend to remain silent. The model is based largely on the premise that individuals are reticent to ex- press their minority beliefs out of fear of isolation—no one wants to be the person who hates something that everyone else loves. Similarly, it’s hard to admit you love something that (you think) everyone else hates. Sunken in the spiral of silence, the individual is most likely to speak only those words that are uttered by the masses, or else their thoughts remain unsaid, their raw reactions suppressed. It was Noelle-Neumann’s belief that the mass media worsened the muting of the minority, since print and digital media provide most of our knowledge about the world and the culture that we in- habit. Like other European scholars of her time, Noelle-Neumann admitted that the written word’s power to change attitudes may be limited to selective exposure. Given the far-reaching influence of mainstream newspapers and magazines, and the widespread presence of advertising—plastered on almost every corner of the contemporary landscape—it’s easier for us to avoid contrary, non-mainstream opinions, and harder for us to formulate and voice thoughts of our own. By employing the succinct syntax of political slogans and news headlines, Holzer’s work interrupts this passive consumption and embracing of popular opinion, challenging the homogenised dialect of mainstream society. In the artist’s own words:

‘I believe people’s beliefs are at the root of their actions. I hoped that since there are many conflicting statements [in the Truisms] that people would pick things out and in understanding themselves, they would know how to proceed [with their actions]. I was also hoping there would be a tolerance, since it would be hard to see someone with opposing viewpoints as a monster if the opposite viewpoint was right below [yours] and also rang true.’

left: from survival by jenny holzer, 1983–85 — right: from truisms by jenny holzer, 1977–79

The sensation of sinking into the spiral of silence is not something that many of us sense. Which is most likely why, when encountering the work of Holzer, we’re forced into a palpable (and at times involuntary) reflection, prompted by both the perplexity and prurience her words provoke. By displaying her Survival series alongside the pre-existing messages that dominate the New York cityscape, Holzer invites bystanders to properly consider their beliefs, and not just to consume. By using text to do so, as opposed to paintings or photographs, Holzer is able to infiltrate the minds of the majority more directly. When asked in the past about the beauty of words specifically, the artist said that when you get them right, people understand. Speaking with Kiki Smith of Interview mag- azine in 2012, Holzer mused, ‘I used language because I wanted to offer content that people—not necessarily art people—could understand.’

In this sense, despite its communal placement, her work does not talk to a crowd en masse; rather, it talks to you. An encounter with her words is often as unexpected as it is intimate, not because of where you are when you read them—on a sidewalk, in a gallery, or in the overcrowded MoMA design store—but because of the part of you that they touch; penetrating your psyche quietly, whispering loudly to your soul.

In an article entitled ‘Fears of a Modern Society’, Milan Ambrož and Boris Bukovec—Professor and Dean of the Faculty of Organisational Studies in Novo Mesto, Slovenia, respectively—state that modern society engages in polishing what they refer to as the “cage of fear”. The way our modern civilisation operates, according to the professors, diminishes the influence an individual has on her or his own life. The rationale behind their con- clusion was that our world has trained us to believe that we cannot protect ourselves, teaching us instead that officials and professionals—politicians, law enforcers, household brand names—always know what’s best. As such, a burgeoning “culture of fear” has taken root in western cultures, stagnating our ability to realise our world through the lens of our own intuition. Ac- cording to sociologist Barry Glassner—the first to establish the construct of a culture of fear—an immense amount of power and money awaits individ- uals and organisations that can tap into our moral insecurities for their own benefit. In his own words:

‘By fear mongering, politicians sell themselves to voters, TV and print newsmagazines sell themselves to viewers and readers, advocacy groups sell memberships, quacks sell treatments, lawyers sell class-action lawsuits, and corporations sell consumer products.’

Projection at Wawel Royal Castle, 2011 by © Jenny Holzer, via DAZED

As a result, Glassner believes that people are more afraid than ever before, burdened by countless anxieties, most of which bloom from the seeds of someone else’s unfounded speculations. Even so, this culture of fear may cause an inherent unrest within us, a distrust of the other, and the eventual erosion of our own instincts. In a world where we’re so often lured into a false sense of insecurity, it becomes near impossible to anchor our inner knowing, to honour our own sense of right and wrong, in a way that remains true to our souls and not just to the status quo.

It’s this dormant intuition that the words of Holzer resurrect, and why I couldn’t ignore that t-shirt in New York when it told me to remember to react. En route to the shop exit, it arrested my attention—an abrupt reminder of my right to a raw, unhomogenised response, and an invitation to sit with the thoughts I was too timid to touch. The three words and six syllables may equate to a basic sentiment, but often the simple things in life are the most crucial to the survival of the self; the small things we lose sight of in the chaos of mass-produced culture.

There are different kinds of ways to feel afraid. Some fears you can see, others you can touch, but sometimes the most fatal are the ones that you don’t know you feel. By reminding us to remember to react, Holzer does not just ask us to speak: she prompts us to realise thoughts we have suppressed, evoking feelings that cower in the shadows of the mainstream mindset. Her art empowers us to become what Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Jung once referred to as a legendary hero of mankind, rising up like a mountain peak from the mass that clings to its collective fears, laws, and methods, choosing their own way; liberated from convention. Holzer once said that she writes to make a portrait of the world. When we remember to react, we make a portrait of ourselves.

This article was first published in issue four of JANE magazine.

Issue seven available for purchase now.